The city of Brussels is not an uniform city. In reality, it is a complex patchwork of independent municipalities varying in size of which the city of Brussels is the largest. In 1989, this patchwork was partially united into one region with its own territory and its own parliament. The political complexity is amplified further as the Brussel region is officially bilingual, French and Dutch. Despite this complexity but due to its political and financial independence, the region of Brussels deploys architecture as a political vehicle to support this identity. Like many other European regions and cities such as Barcelona and Slovenia, the city somehow managed to develop its own identity in terms of architectonic culture.

Despite a rich architectonic history – such as the byzantine Palais de Justice by Poelaert in the second part of the 19th century; the Art Nouveau experiments by Victor Horta at the close of the 19th century; the World Expo of 1958 introducing the world icon of the Atomium; or the relative success of participative movement as initiated by Lucien Kroll – the architectonic landscape Brussels was in disarray at the beginning of the 1980’s. From 1980 onwards a more restrained and esthetical architectural language such as postmodernism takes hold amongst architects. In an often legitimate opposition to the excesses of modern architecture – such as radical urbanism wiping out many singular houses replacing them with high rise tower blocks combined with large infrastructural works to increase car and train mobility largely to the detriment of the pedestrian – the city gradually fell in the trap of false nostalgia and retro movement. In many cases Brussels postmodernity, proved to be an superficial and overly aesthetic movement. It soon became a pretext for commercial stakeholders to shamelessly realize their agenda behind a pretty facade.

From the 2000’s onwards, the negative public perception in Brussels surrounding architecture changed. Recent edifices such as De Geyter’s subway terminus at Place Rogier or V+/ROTOR’s MAD Design Museum both finished in 2017 ‘liberated’ architecture from its political and financial ties. Buildings such as these implied a return to the heydays of 50’s iconic architecture.

Three important factors contribute to the recent formation of a proper Brussels architectonic culture. First, the introduction of a city architect. Secondly, increased participation of the citizens in the decisions making process. Thirdly, the anchoring of European institutions in the city of Brussels.

First, following the Dutch example, a city architect was installed in 2009. The current city architect, Kristiaan Borret advises -together with his independent administration- the city about what and how should be built in a broad dialogue with different stakeholders. He introduced new themes for a larger audience such as architecture on a metropolitan scale, the productive city, densification and maximisation of public space.

A second element which shifted the architectural scene was the so called Event ‘Pic Nic The Streets’, as organised by a group of dissatisfied citizens, demanding more space for the pedestrian and cyclists. In 2012, these citizens occupied a busy crossroad at the very centre of the city near the Bourse. Finally, the city of Brussels gave in to their demands and created space for one of the largest pedestrian zone of Europe. The final design of this pedestrian zone has been finished, and should be realised soon. Surfing on the waves of this success, more citizens oriented projects saw the light. The exquisite Parck Design project near the Tour and Taxis site envisages the rehabilitation of a derelict railway zone into an ecologically inspired park and farm zone as supported and maintained by the locals from the neighbourhood. This evolution is not without coincidence. In Brussels, there has been already an expertise in participative projects such as the renowned la Mémé university housing project in Woluwe, through the architecture of Lucien Kroll, who was inspired by the sexual revolution of May 1968.

A third element is the growing presence and ambition in Brussels of the European institutions such as the European council, Parliament and Commission in Brussels. Since the 50’s, the presence of these European institutions were in limbo, as Brussels was never formally confirmed as capital of the European Union. Unfortunately, This meant that architectural quality was not a high priority: the blunt appearance of the Justus Lipsius building speaks for itself. Moreover, in the past, a novel EU building nearly always implied the demolition of nearby housing. However, since the Nice treaty of 2006, Brussels has been formally appointed as the official headquarter of the European institutions. This provided the impetus for the European institutions to fully invest in the city. From then on, the EU took full ownership of their buildings and responsibility towards the immediate neighbourhood of Ixelles.

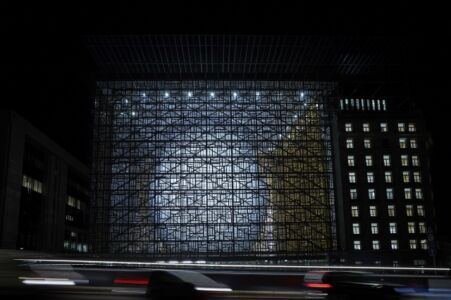

The most recent building for the European Council, the Consilium was designed by a consortium of the Belgian architect Philippe Samyn, Italy’s Studio Valle and UK Based Buro Happold in 2004. As the European council hosts and accommodates a growing number of large international meetings of the EU, a new extension was necessary. Its delightful façade made of recycled oak doors and window frames radiates confidently towards the public eye. The egg shaped internal lantern glows in the evening, metaphorically providing light and shelter to the distribution of European ideas and values. However, the symbolic shape of the lantern was largely determined by other factors such as security issues and logistical requirements of plenary meeting rooms for the 26 EU members with varying sizes.

Interestingly, it is the first EU building in its kind. Because it is a refurbishment of an existing building i.e. the adjoint Art Deco building, named Residence Palace as designed by Michel Polak in the 1930’s as a luxury residence with swimming pool and shops. It is in reality a twin building where the old meets the new. In fact, Samyn purposefully designed the interior as to seamlessly unite the delicate Art Deco interiors with the formal requirements of EU offices for the European council. It was also the first building entirely funded by the EU (not the Belgian state). Finally, it was the first without the necessity of demolishing the surrounding urban fabric. The colour concept of carpets and ceilings in the meeting rooms are designed by an artist, Georges Meurant purposefully portraying softer pastel colours which bear no reference to the respective European national flags.

In the backdrop of this new dynamic -the new city architect, the growing emancipation of its citizens, the advent of the Consilium- Europe seems to orientate itself to Brussels as a welcome guest and arguably not as an intruder, thereby implying a late yet authentic arrival of an EU inspired architectural legacy.