After participating in the Art Biennale in 2013 and 2015, the Holy See will be present for the first time at the 16th International Architecture Exhibition with “Vatican Chapels”, a “widespread pavillion” on the Island of San Giorgio. Some reflections following the press conference on March 20th

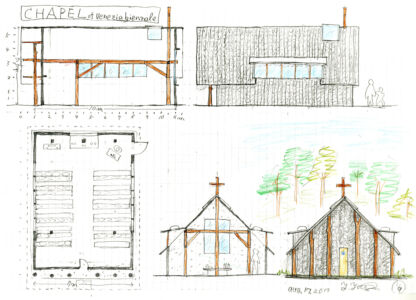

As already inevitably echoed in a multitude of publications, the next Architecture Biennale in Venice will be celebrated as the first one to register the participation of the Holy See. This will take place in a dispersed exhibition throughout the gardens of San Giorgio Island, with ten isolated chapels, entrusted by the curator Francesco Dal Co to ten well-known or up and coming architects, that vary in generations and gender, and an entrance pavilion dedicated to the Skogskapellet (the wood Chapel in Stockholm) by Gunnar Asplund (1920) and designed by MAP studio (Francesco Magnani and Traudy Pelzel).

If the participation of the Catholic Church in the Venetian event finally fills the absence of the most important architectural client of the last eighteenth centuries and it is a success that also Cardinal Gianfranco Ravasi (president of the Pontifical Council for Culture and Commissioner of the Pavilion, ed.), has ascribed coram populo to the president of the Biennale Paolo Baratta, the way in which this presence is announced deserves some reflection.

First of all, the particular theme that the curator assigned to the invited architects appears to be slippery. In the Catholic orb, that of chapels is an architectural theme always corresponding to a specific purchasing body within the universal Church. From the Episcopal chapels of the Syrian Tetrapolis (5th century), to the palatine ones, (from the 8th and 12th centuries); from the chapels of noble families to those of popular piety and devotion, the refining of an architectural type has always corresponded to an identifiable customer. Outside of this anchorage, elitist or as popular as it is, chapel remains the title for spaces generally representative of the universal metaphysical tension of humankind, as it is shown by a catalog that has become extensive and which our Journal has already mentioned in the survey of contemporary churches: from the ’55 chapel by Eero Saarinen at MIT, a multitude of ecumenical or non-denominational “chapels of silence”, can be intercepted in hospitals and places of care in the role of stop-overs for estrangement and catharsis, as in suspended and waiting spaces (airports, stations) that someone can claim to be a metaphor of existence.

A certain ambiguity in the genre “chapel” was already present in the ecclesial tradition. Since the term Capilla appears, it does not designate a space specifically assigned to a liturgy, as it gradually happens for churches. The term rather identifies a place of modest size, where prayer can be favored by the presence of transitional objects, such as relics or, precisely, the famous (half) Cappa of St. Martino whose prestige was such as to force metonymic exchange between containing and content and transform the oratory of the Merovingians which contained it in the first Capilla that history recalls.

Chapels displays the lowest common denominator of faith. If this was once, in Europe, a Christianity with wide banks, capable of absorbing the thrusts of superstition and of creeping popular polytheism, today, in a global society, it has become a vast basin of divergent currents, hopes and private beliefs, or emotional, mainly de-institutionalized. Now, the fact that the Vatican demonstrates to be concerned about offering a home to these trends, may seem paradoxical even if, in some way, it can be read in coherence/continuity with the Council mandate (Gaudium et Spes, 1), with the current Papal Magisterium ( centered on the theme of suburbs also interpreted as an existential condition) and, last but not least, with the “Cortile dei Gentili” [Gentils Courtyard, ndt] , the initiative that Cardinal Ravasi founded as an institutional platform to foster dialogue between believers and non-believers.

Giving the theme of a chapel today, without further specification, means requiring a spatial interpretation of the complex and controversial spiritual horizon of contemporary humanity, that is, of a general aspiration to heaven that does not always intercept, as provocation or possible response, the opposite movement of a God who made flesh. So the cross is a sign that some designers consider, someone else not, Francesco Dal Co declared, like the altar and the book, only objects cautiously suggested by the client.

For the rest, the designers were left alone before the enormity of the order, at the mercy of their genius in the most romantic of the stereotypes, facing a community dilated in the world, and without an initiation to the semiophores objects even if / although recommended. A solitude also reflected by the surrounding gardens, a wild area behind the Monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore, where the chapels will be located for a long time (…beyond the limits of this Biennale, as already predicted Dal Co…) only the horizontality of the Venetian lagoon. In these circumstances, the alphabet of archetypal signs always provide a first aid, updated by the new thin and light performative materials through which the intrinsic sacredness of architecture is definitively celebrated more than the architecture of the sacred, that is, the power that it has to define, determine and measure the space to conquer it to man, as Genesis already taught (28,10).

Even in the vein of a Church that wants to strengthen ties with the world of creativity and art, in the wake of Paul VI, we must take note that, compared to the path desired by the latter and on which the Offices for Cultural Heritage and the Cult Building of the CEI have long since set in motion, this initiative moves against the current: it is not the contents and signs of the Church’s tradition that are subjected to the artists’ poietic activity to obtain new spatial interpretations, but it is the free poietic activity of the artists which is expected to dress with new intuitions the faith of the Church.

However, it is also possible that the one just mentioned is just one of our over-interpretation, because the emblem of the whole exhibition will be the Chapel in the forest by Gunnar Asplund: a space that, protestant and (above all) funerary, messes up the cards again and opens a new meatus in the coherence and in the organic nature of this program. In the final analysis, the only sacredness that the pavilion certainly celebrates is that inherent in architecture and the announced Revelation is that with which this art reveals, signifies and measures space for man.

Vatican Chapels designers:

Andrew Berman (New York 1969), Francesco Cellini (Roma 1944), Javier Corvalan Espinola (Asuncion, Paraguay, 1962), Eva Prats e Ricardo Flores (Barcellona), Norman Foster (Gran Bretagna 1935), Teronobu Fujimori (Nagano, Giappone 1946), Sean Godsell (Melbourne 1960), Carla Juaçaba (Rio de Janeiro 1976), Smiljan Radic Clarke (Santiago del Cile 1965), Eduardo Souto de Moura (Porto 1952), MAP studio (Venezia 2004, Francesco Magnani e Traudy Pelzel)

Cover photo: the Chapel in the forest by Gunnar Asplund, Stockholm, 1920

About Author

Tag

biennale venezia 2018

Last modified: 8 Aprile 2018