Second fire in four years for the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh. William J.R. Curtis asks himself: accident or error?

This morning I woke up in the early hours and decided to consult the news on the web. To my astonishment I saw those horrendous images of the Glasgow School of Art going up in flames again. It was like a bad dream: a glowing orange inferno caught on mobile phones. It brought back memories of the fire four years ago which destroyed the most beautiful space in the building, the Library, in fact one of the great spaces in the entire history of architecture. But this time the damage has been more far reaching. In fact it looks as if the entire interior has been gutted. The building was in restoration but now it has been utterly destroyed. All that remains is the masonry shell and this will have been dangerously damaged by the very high temperatures. In reality, I fear that this masterpiece has gone for ever.

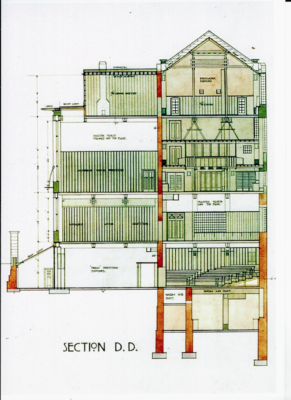

I am devastated by this loss. The Glasgow School of Art was like an old friend and every time I visited it I discovered a new dimension of the work itself and of architecture in general. The Library was an inspiration: the abstraction of a woodland clearing with something of the character of a Japanese temple. The exterior of the west wing was a masterpiece of ambiguities between figure and ground, space and mass. Mackintosh’s building was in and of itself a teaching building: it tought students to see, to experience space and light, to feel textures, colours and materials. It touched the mind and the senses of all who passed through. It rested in memory. This was high architecture but it was somehow casual and convivial. It encouraged the mess of creation in its studios and promoted the mixing of people on the landings and stairs. It became a collective landmark, but only after decades of neglect during the years of Glasgow’s decline.

In 2009 the Glasgow School of Art celebrated its centenary and I was honoured to be invited to deliver the keynote address to which I gave the title ‘Materials of the Imagination: the Glasgow School of Art by Charles Rennie Mackintosh’ *** (see http://www.gsa.ac.uk/life/gsa-events/events/w/william-jr-curtis/?source=archive). I took the long historical and geographical view. I disturbed some of the cosy Mackintosh legends attached in recent years to the ‘brand’. This is or was one of those works that escape all stylistic categories. Its importance transcends local Scottish, British or even modern architectural agendas: it is, or was, a major universal creation, a part of human patrimony. There has been no work in the British Isles since to touch it, although there have been remarkable buildings influenced indirectly by it such as Stirling’s Leicester Engineering or Lasdun’s masterpeice the Royal College of Physicians both of the early sixties. **** For Curtis keynote see http://www.gsa.ac.uk/life/ gsa-events/events/w/william-jr -curtis/?source=archive

The Glasgow School of Art does of course have a major place in my book Modern Architecture Since 1900 (Phaidon 1st ed 1982; 3rd ed 1996) but I always refused to see it as Pevsner did as a mere ‘pioneer of modern design’. It may have seemed in retrospect to be anticipating some features of modern architecture but it also looked sideways and back. Like all unique masterpieces, the building does not fit a single chronological slot. Its cousins may have been Josef Hoffman in Vienna and Frank Lloyd Wright in Chicago but it also contained many historical echoes. In British architecture one has to go back to Soane or Hawksmoor to find anything of this astounding originality and quality, but it is an inventiveness rooted in a deep sense of the history of architecture. Mackintosh fused a unity out of a wide range of sources from Scottish Baronial castles, to Japanese architecture, to North American and British industrial buildings, to Michelangelo, but he transformed these into something fresh and new. He also crystallized an era in a Glasgow that was linked to the wider world through the steamship routes of Empire while hankering after myths of national identity in the vernacular and nature of the Scottish heartlands.

The Centennial events of December 2009 were wonderful as they brought together students from all over the world with major figures of Scottish and international architecture. Somehow the building looked at its best in the frost and mist of the Glasgow winter, especially at dusk when the lights inside conferred an oriental atmosphere like a lantern. The students interviewed me in the warmth of the timber library with its crystalline abstractions of oriel windows and I spoke for half an hour about my admiration for the building and about the way that it was like a quarry of inventions and inspirations, many of them yet unrealized. A building with a great future then!! Then in the ensuing months and years there was the messy business of Holl’s over scaled and hostile annexe across the road, a cold glass refrigerator of a building without any contextual sensitivity: a supposed flagship created by a member of the international ‘star system’. (William J.R. Curtis, ‘Facing up to Mackintosh’, Architects Journal, Nov 5th 2010 http://www.architectsjour nal.co.uk/news/opinion/facing- up-to-mackintosh/8607805 article and Curtis, Glasgow Neighbours – Mackintosh versus Holl’, Architectural Record, February 2011 http://a rchrecord.construction.com/fea tures/critique/2011/1102commen tary.asp).

The Holl project was bad enough in itself, but so was the failure of authorities on all sides to reign this monster in. Then in 2014 there was the fire, apparently started when a student project went wrong and a projector caught fire under the influence of a chemical spray. Of course one wondered what such materials were doing in wooden parts of the old building at all, especially when less inflammatory studio spaces for experimental work were available elsewhere. In reaction to this tragedy I published an article in the Architectural Review July 2014 entitled ‘Burning Questions’ (https://www.archi tectural-review.com/essays/ burning-questions-reconstructi ng-the-fire-scene-at- mackintoshs-glasgow-school-of- art/8665000.article). Was this just an accident? Was there responsibility at some level? Quickly such questions were smuthered under political rhetoric and the promise of major public funding to restore the building, as if that were really possible. But if there was a choice between a competent pastiche and a new project, the former was nonetheless considered somehow preferable.

So over the intervening years groups of dedicated architects, consultants, engineers, historians, restorers and craftsmen have been at work trying to bring the corpse back to life. Last night their devoted work was undone in a conflagration which spread through the building in a short space of time. Once again the heroic firemen did all they could to save this masterpeice, a work much loved by Glaswegians but also by people all over the world. Is anyone to blame? Or is this just to be called another ‘accident? What are the burning questions for the inquest that has to follow? It is important to ask precisely how, when and where the fire got started. One also needs to know how it could have spread so quicky through the interiors. Were fire protection devices such as sprinklers actively in place and activated? If so, why were they so apparently ineffective? If they were not in place and/or not functioning, then one needs to know why? Were their watchmen and cameras? When was the fire first spotted? And so the list could go on. In the case of the first fire a sprinkler system was installed but not yet functioning; we have just learned that the same was true with the second fire. In 2014 everything was done to avoid answering the burning questions and to avoid any suggestion of personal or institutional responsibility or liability. This time there should be a full public inquiry insisting upon accuracy and possible accountability. But whatever the verdict of such an inquest or enquiry, this time I fear that Mackintosh’s majestic masterpiece the Glasgow School of Art has left this earth forever, body and soul.

Copyright: William J.R. Curtis 16th June 2018

For further reflections on the long term historical importance and value of the Glasgow School of Art, see:

Centennial Event, December 14th 2009, Keynote Address: William J.R. Curtis, ‘Materials of the Imagination: Glasgow School of Art by Charles Rennie Mackintosh.’ http://www.gsa.ac

Foranother version see lecture at Spitzer School of Architecture, City College New York, April 11th, 2011 http://www.totalwebcastin

For criticisms of project by Stephen Holl see William J.R. Curtis, ‘Facing up to Mackintosh’, Architects Journal, Nov 5th 2010 http://www.architectsjour

For Curtis ‘Open Letter to the Governors, the Director, the Faculty, Students, Staff, Alumnae and Alumni of the Glasgow School of Art’, February 28th, 2011, see Architect’s Journal, March 3rd, 2011 for Facsimile of this letter http://m.architectsjour

[…] LEGGI L’ARTICOLO IN LINGUA ORIGINALE […]

[…] Holl Architects (2009-2014) accanto alla Glasgow School of Art di Charles Rennie Mackintosh – recentemente devastata dal fuoco – e il Riverside Museum firmato nel 2011 ancora da Hadid nel quartiere del risanamento di […]