A new generation of Italian architects asserts itself on the international scene, it marks a return to architecture as a profession and often builds up its fame and gains clients by means of international competitions. Architecture without compromises both in respect of the industrial design and the iconic exasperation, it pays attention to the budget but does not renounce to invention and experimentation. We start from the OBR studio, whose language excludes the Brutalism high tech, despite occasional delay in modernist pleasures of beton brut, encountering Paolo Brescia in his studio in Milan, located in a discreet yet central street of the historic center, a few steps from the Duomo. It’s a vocation or concession to the charm of the ancient and the tradition, in their works the theme of the elements assembly sometimes prevails, sometimes the node and the graft with dynamic textures, sometimes with excursion into the concrete casting, as if the emancipation from modernism of contemporary project could turn eclecticism in a new virtue without constituting a trend or revival. So, the themes of form-function correlation and interior-exterior dichotomy crystallizes in the conflict between the body and the skin of the building and look for a balanced mix between classic structural evidence and surface immateriality, emphasized in Ospedale dei Bambini and ex Cinema Roma in Parma, in the Milanofiori housing complex, up to renowned Ristorante Terrazza Triennale, awarded with the Premio Internazionale di Architettura e Design InArch 2015). A path without concessions to referential spectacular events, vernacular degeneration, emphatic decontestualization, playful and technological overstatements. Is architecture still serious?

How would you describe your work today, in regard to the legacy of the Modern Movement and also to the main architects that came after the Movement, like Renzo Piano, for example, who is a master in recent times? The attention to the process and the technological experimentation, like the acronym OBR Open Building Research, recall your experience with him, but what are the main aspects of Piano’s works in which you recognize and those from which you distance yourself?

OBR is a collective born from the idea to investigate new ways of contemporary living by creating a network between Milan, London and Mumbai. Tommaso and I had met while working with Renzo, with which we are still working on some projects. Working with Renzo gain a method, that of téchne, in the classical sense of “know how”. With Renzo learn to apply research, make architecture applied. When we start a new project, we meet, we discuss, we define a vision, develop strategies, and the design is the outcome of this process. There isn’t a standard idea through which you try to get to the result. The output of the process is more interesting than the input

This means that the vocabulary and the design choices are inconceivable: how do you define this process, which then leads to the synthesis of the form?

I would say “serendipitous process”. The architecture is the outcome of that process.

Therefore this involves a continuous updating of the language in regard to the challenges that the project issues. The repertoire is available, but it is continuously challenged.

I think that today we suffer from a problem: the gap between the vision that develops when you start a project and the representation of that vision, that is the gap between the what and the how. We are too tied to a canonical vocabulary of the representation of architecture that is no longer able to represent reality, especially if the reality that you investigate is the one that is coming up.

Therefore it was essential to rejoin to the design methods of other disciplines: music, art, sociology, technology but also to the skilled craftsmanship. How do these requests emerge in the contemporary project?

To answer your question I would like to refer to a project that we started on behalf of the Li Ka-Shing Foundation of Hong Kong for the Shantou University. After winning the competition of design ideas the operational meetings with the client were unsuccessful. Basically we did not understand each other: they asked us for a space in which people could meet and we proposed them a project that kept the threshold between inside and outside indefinite and accommodated the community of University. Anyhow, it was a real building with a Hall, space outside and inside. The problem was that we were designing with the instruments of architecture only. One day, in order to make themselves understood, they asked: would you be able to create a kind of actual Facebook physical space, where people meet to share experiences, interests, values? The solution was a space that we imagined as a tray, completely open on all sides, on which is suspended a volume that, as a scenic Tower, lowers all the necessary devices that define many different spaces for many different uses of the same space-tray.

Managing the aesthetic result of these shared open source processes is quite hard…

If you participate in the process, if you listen, if you are going through a serendipitous research, new questions come up with unexpected solutions.

Your description makes it easy enough. Despite the situation in Italy has little to do with serendipity, you could perform excellently also in Italy. So, is the method important?

We could do something in Italy when the Public Administration already had a strategy, for example in the case of the Museum of Pythagoras. In that case the Administration designed a strategy of urban regeneration. It launched an international competition funded by the European Community, which aimed to activate a process of urban regeneration in Crotone through the enhancement of the figure of Pythagoras, and promoted the city in the framework of the international circuit of cultural tourism. Locally the choice of locating the Museum over the suburbs, as a new urban polarity, activated urban flows from the old city and regenerated by irradiation a large urban area that suffer heavy social diseases (this works very well from the point of view of social inclusion).

However, in this case, you chose a modernist language that is consolidated, traditional, iconic, symbolic.

Apparently yes, but it was essential to integrate the project into the suburban context that we were facing and at the same time to create a new urban polarity: basically adhere to the orography of the site and at the same time be evident from the historic centre to enable new urban flows through the suburbs. For this reason we designed a building both over and under the ground level. For this double meaning, global and local, the building works both as a scientific centre and as an aggregation centre, in which people of the neighborhood meet (even when the Museum is closed, the cafeteria-belvedere is accessible from the public park). That “modernist” form stems from the need to give a double point of view to the true altitude of the city: the entrance to the Museum from the old city, or the entrance of the cafeteria from the neighborhood?

Your attention to the user makes you different from the masters of the Modern Movement, who often prevailed on the individual in the name of their absolute imperatives: the contemporary project is now more user oriented?

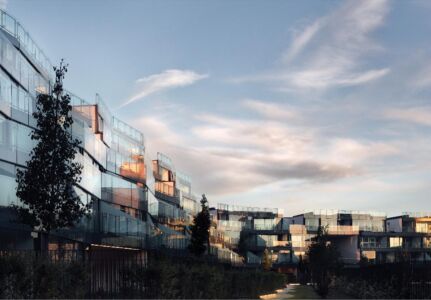

I give you another example. When we took part in the competition for the urbanization of Milanofiori, the theme was the living. The customer asked 10 architects to decline a new way of living in a place without any urban identity. This experience of Milanofiori was significant for us because we did not have much experience in residential building at the time and we approached the issue by asking ourselves: what would you do if it were your house? The common answer identified a space that was interactive with what goes on outside, as it were an organism that acts (and reacts) dynamically with the context, according to a principle of action-reaction. The topic was how to create the idea of place by starting from the dwelling, the idea of caring for that place that the dwelling entails. For this reason we decided to lead the public relations into the private dwelling and the private relations among the public ones, and created the sense of neighborhood by using the court, but not as it worked for the multi-storey buildings with accesses from balconies, but rather by means of the private spaces, where the inhabitants themselves, in different ways, describe their community, share the same values in the same place, give more value to the specific individual identities.

Share the private space as much as possible …

By expressing your identity. Talking about you. You are the inhabitant, you choose.

This is also the definition of Kenneth Frampton: architecture is nothing but what is common, public, sharable, beyond the exclusive private use.

The lifestyle devise the habitat, not vice versa. I want to be the subject of my way of living, and not the object of a preconceived model. Is the end-user, the inhabitant, who decides how much to exchange with whom and with what. I want to be the author of this choice.

Indeed, perhaps this is precisely what makes a space stronger, defined by the customization.

I remember the last time we were in Milanofiori we met a guy who saw us loiter in the Court and he wanted to show us his house. When I asked him where he lived, he didn’t say “I live on the second floor the third window on the left”, but “I live there, where there is the Red Maple and the kitchen table”, identifying his house with what he decided to show us. Another girl, instead, told us about the vocabulary of closeness and belonging that grew in the neighborhood through non-verbal communication between the inhabitants, from home to home.

So, the concept of flexibility in architecture is the ability to manage this relationship between public and private. If the architect does not take care of this aspect, he fails its social mandate. In my opinion this should mark the end of the archistars, who are more concerned to “sell” their products and impress the seal of trademark for a universal audience.

I think that things are changing today. The phenomenon that we are experiencing in recent years is the awareness of the national identity, especially in the emerging markets, in Asia, in Africa. Moreover today the International urban marketing opts for a focus on differentiation and uniqueness, by starting from the specific cultural and social identity of the promoter (public or private).

Which is a differential identity, which is made of contrasts between tradition, history and needs of today …

For example: when the young Indian generations who studied in Europe decide to return to India, they want to find the values of belonging to their own cultural traditions, but declined in a contemporary way. What is interesting is not a project for Jaipur, but by Jaipur.

After all the playful overstatements and the imposed morphogenetic idea of the industrial design are quantitative and qualitative aspects of the contemporaneity. How do you read into this phenomenon? More and more often the architect is involved in projects-processes that require only a lay-out, an iconic image … What are the strategies to restore the architecture out of the purely formal exercise?

I believe it is important to change the point of view from what is fancy to what is significant. Commercially, it is convenient also for the developer to step back from what is purely fancy and pay attention to the people’s real needs and ambitions. People ratify the success or the failure of an operation. We recently developed a master plan for a project in Ghana, a new cluster for 65,000 inhabitants. To limit the urban sprawl, you have to try to limit the city by working on the edge, but in the classical meaning of limes, “where something else starts”. At the same time, it is essential to find a place where people can develop the idea of community outside the hotel lobbies or the malls, recreating the urban status that always existed. In that case, the priority is not so much the building itself, but the different arrangements of buildings in the landscape. This phenomenon is quite evident in West Africa, in what anthropologists define as Compound House, a traditional home made by the union of elements reproduced as fractals, by means of self-similarity and self-reproduction, according to a progressive composition that generates a central space: the space of social interaction. It is not too different from the proxemics of Edward Hall.

The lack of a traditional urban memory triggered new opportunities for creating a public space in which to test possible ways of social development, no longer starting from a standalone functional program, but as a result of behavioral situations caused by local collective life, from which you can create an urban effect by interpreting a traditional aggregation model in a contemporary sense and catalyzing the impulse towards a greater social involvement. This experience allowed us to go beyond the classical opposition public/private, individual/society, environment/architecture, that is towards a new dimension of the common good, understood as social capital, as a place that is shared by all members of the community.

What are you working on currently?

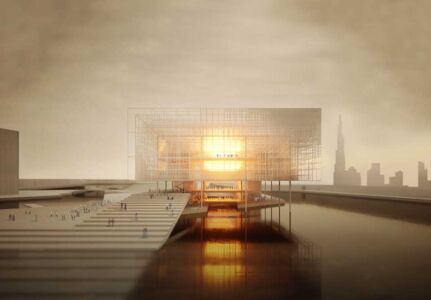

At the moment we are engaged in the Emirates and in Italy. In Dubai we are following the project of the development of the free zone of Jafza opposite (in front of) Dubai Expo 2020. It is a multifunctional centre which extends 3 km along the high way to Abu Dhabi. We’re imagining it like a strongly urban place, promoting the meeting, exchanges and an unexpected discovery of something that you’re not really looking for, which is the essential feature of public space. For that reason we have designed a promenade outdoors but covered, naturally lighted and articulated in a series of internal squares on several levels that allow different ways of mobility alternatives in continuity with the Expo 2020. We would like to show that even in Dubai it’s possible to extend some group activities, not by importing foreign models, but developping local site specific forms reinterpreted in a contemporary key. In Italy we are working on the design of the new Hospital Galliera, Genoa. It is a very complex project in the heart of the city, where we’re combining innovative healthcare needs (hospital network) who require an urban insertion. The specific characteristics of the neighborhood of Carignano represented an opportunity to define the correct urban scale, decomposing the volumes in order to make clear the tip of the iceberg. In practice, leveraging the existing topography we created a semi-underground health plate above which a new urban land is developed becoming a garden in the city. The only things visible are the wards, which will occur as pavilions in a park. It will be a big hospital inside and small outside.

![]()

After working with Renzo Piano, in 2000 Paolo Brescia and Tommaso Principi established the collective OBR Open Building Research to investigate new ways of contemporary living, creating a design network between Milan, London and Mumbai. OBR develops its experimental line through the participation in projects concerning public-private social programs, promoting – through architecture – the sense of community and the individual identities. Paolo graduated in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano in 1996, after academic fellowship at Architectural Association in London, while Tommaso graduated in architecture from Università di Genova, after several feature films Paolo and Tommaso are guest professors at universities, such as Academy of Architecture of Mumbai, Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, Aalto University. OBR’s projects have been featured in Venice Biennale of Architecture; Bienal de Arquitetura of Brasilia, MAXXI in Rome, Triennale di Milano. OBR has been awarded with AR Award for Emerging Architecture at RIBA, 2007; Plusform under 40, 2008; Europe 40 Under 40 in Madrid, 2010; Leaf Award in London, 2011; WAN Award Residential, 2011; Green Good Design Award in Chicago, 2012; Ad’A Award for Italian Architecture, 2013; Inarch, 2015.

After working with Renzo Piano, in 2000 Paolo Brescia and Tommaso Principi established the collective OBR Open Building Research to investigate new ways of contemporary living, creating a design network between Milan, London and Mumbai. OBR develops its experimental line through the participation in projects concerning public-private social programs, promoting – through architecture – the sense of community and the individual identities. Paolo graduated in architecture from the Politecnico di Milano in 1996, after academic fellowship at Architectural Association in London, while Tommaso graduated in architecture from Università di Genova, after several feature films Paolo and Tommaso are guest professors at universities, such as Academy of Architecture of Mumbai, Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, Aalto University. OBR’s projects have been featured in Venice Biennale of Architecture; Bienal de Arquitetura of Brasilia, MAXXI in Rome, Triennale di Milano. OBR has been awarded with AR Award for Emerging Architecture at RIBA, 2007; Plusform under 40, 2008; Europe 40 Under 40 in Madrid, 2010; Leaf Award in London, 2011; WAN Award Residential, 2011; Green Good Design Award in Chicago, 2012; Ad’A Award for Italian Architecture, 2013; Inarch, 2015.

[…] LEGGI L’ARTICOLO IN LINGUA INGLESE […]