The Turkish metropolis between contested mega-projects and inclusive micro-interventions for public spaces. With the arrest of mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu marking a breaking point

The plans of French architect Henri Prost, who reimagined Istanbul’s urban landscape in the mid-20th century, are regarded as foundational to the city’s modernisation. However, Istanbul’s transformation today is shaped not just by Prost’s legacy but by a dynamic tension between large-scale interventions and localised urban strategies. The city is currently transforming through a combination of large-scale government projects and smaller initiatives that mirror changing political and social priorities.

Henri Prost’s Modernisation Process

Henri Prost was invited to Istanbul in 1936 and developed planning strategies that gave the city a new identity during its transition from the Ottoman Empire to the Republic. His approach was based on three core principles: transport, environmental health, and aesthetics.

Prost aimed to adapt the city’s transport network for motorised vehicles, restructure urban development to meet public health standards and integrate aesthetic considerations into urban design. During the 1930s, the city expanded northward on the European side and eastward along the coast on the Asian side. Additionally, fire-damaged areas in the Historic Peninsula created large voids that caused the city center to shift away from these abandoned spaces. To counteract unregulated urban sprawl, Prost proposed concentrating urban development around a new transport backbone.

One of his primary strategies involved creating north-south arterial roads to connect the fragmented urban spaces on both sides of the Golden Horn. In a 1947 lecture at the Paris Academy of Architecture, Prost described Istanbul’s urban planning as a “delicate surgical operation,” emphasizing the importance of preserving historical fabric while recognising transport infrastructure as an economic and social necessity.

His proposals for broad boulevards, green spaces, and public squares continue to influence Istanbul’s main transport corridors and public areas today. However, over the decades, various administrations have reshaped his plans according to their political priorities.

New Dimensions of Urban Transformation

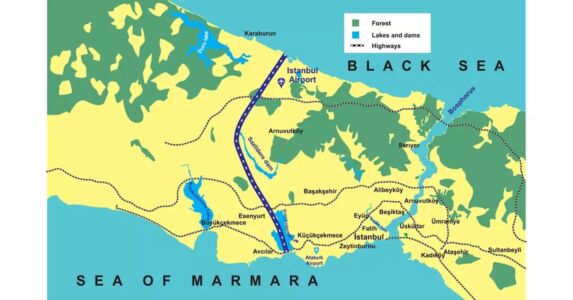

Contemporary Istanbul has moved away from Prost’s centralised planning approach, embracing a fragmented and multi-actor urban transformation process. In the 21st century, large-scale infrastructure projects, particularly those targeting the northern regions of the city, contrast sharply with the urban fabric envisioned by Prost.

Projects such as the Third Airport and Kanal Istanbul, driven by financial and prestige concerns, challenge Istanbul’s ecological limits and fundamentally contradict Prost’s vision for green spaces. These developments place immense pressure on the city’s water basins and forested areas, promoting an uncontrolled expansion model that shifts urban development away from the city’s core. This shift not only disrupts Istanbul’s historical spatial logic but also challenges fundamental notions of urban democracy and the right to the city.

These megaprojects are often presented to the public as symbols of prestige rather than as technical or scientific necessities for urban development. For instance, the Third Airport was promoted with the claim that it would become “one of the world’s largest airports.” However, ongoing critiques focus on its environmental impact and transport infrastructure, and the project remains a topic of heated debate. These discussions extend beyond academic and civil society circles, influencing even the election campaigns of opposition parties.

Micro Interventions: Redefining Public Squares and Urban Spaces

Micro-scale spatial interventions also play a critical role in Istanbul’s transformation. The redesign of public squares such as Taksim, Uskudar, and Kadikoy through design competitions highlights the tension between Prost’s vision for public spaces and contemporary urban policies.

Prost envisioned squares as central hubs for social interaction and public life. However, until the 2010s, interventions primarily aimed to integrate these spaces into commercial networks. The pedestrianisation of Taksim Square and the debates surrounding Gezi Park are key examples of Istanbul’s ongoing struggle over public space.

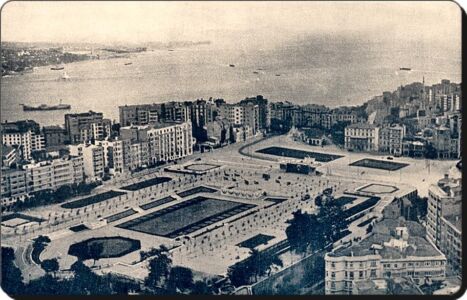

In the 1940s, Henri Prost’s plans reimagined Taksim Square as a vast urban space. Gezi Park was conceived as a large green area overlooking the Bosphorus, while the monument’s surroundings were designed as a ceremonial square enhanced by cultural facilities. New transport connections were also introduced to integrate private and public transport systems.

However, starting in the 1950s, structures such as the Intercontinental and Marmara hotels were built within this public space, weakening Prost’s green space concept and severing Gezi Park’s natural connections with the northern green zones. By the 2010s, Taksim Square had become an island surrounded by traffic.

The pedestrianisation project initiated in 2012 aimed to free the square from vehicle traffic, but the result was a vast yet functionally inadequate urban void. Around the same time, the proposal to reconstruct the historic Topcu Barracks in place of Gezi Park sparked intense public opposition. The 2013 Gezi Protests became a turning point in Istanbul’s public space debates, ultimately leading to the cancellation of the project.

Following the 2019 local elections, a new approach emerged under Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu’s leadership, recognising that the future of public squares could not be dictated by a single ideological perspective. Initiatives such as comprehensive restoration works and public design competitions contributed to the city’s evolving relationship with its spatial and cultural heritage. Mahir Polat, the Deputy Secretary General of the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality, played an essential role in these efforts, mainly through restoration projects and heritage mapping aimed at recovering neglected urban values. The Istanbul Planning Agency (IPA), a department within the municipality, also supported inclusive planning practices by collaborating with municipal staff and independent experts to redesign public spaces across the city.

In particular, the design competitions for Taksim, Bakırköy, and Üsküdar squares, launched by the IPA, exemplified this new vision by incorporating citizen participation, including public voting and open colloquiums. The jury reports for these competitions emphasised designs that respected Prost’s vision not as static heritage, but as a framework open to contemporary reinterpretation and civic engagement.

At the end of March 2025, Ekrem İmamoğlu, Mahir Polat, and four urban planners (two of whom were employed by the Istanbul Planning Agency and two who served as district mayors in the city) were arrested. Much like the controversial ‘mega projects’, the official justification for this political move has been met with widespread criticism.

Henri Prost’s planning principles have left a lasting imprint on Istanbul. However, contemporary urban dynamics continue to reinterpret and reshape this legacy. While megaprojects transform the city’s ecological and social structure, micro-interventions redefine the meaning of public space. The future of Istanbul hinges on whether it fosters a holistic, participatory urbanism or remains trapped in a cycle of fragmented, top-down interventions.

Cover image: Galata Bridge, Istanbul