Reflections on the anniversary of Bernard Rudofsky’s exhibition and book on vernacular architecture that subverted mainstream thinking

How do you start a revolution after being part of what you want to overturn? It takes a lot of courage, conviction, and necessity. You must believe that it is the only way. This means breaking the mold, and it is no coincidence that Bernard Rudofsky (1905-1988) chose the powerful impact of visual associations to support his convictions. Nothing was the same in architecture after Architecture without Architects. Even though the official historiography ignored or sidelined Rudofsky’s grand opening for years, the seed had been thrown and spread worldwide.

MoMA 1964: A Brief Introduction to Architecture without Pedigree; A Departure from Routine

In 1941, when Philipp L. Goodwin requested an uninflated subject for an exhibition at MoMA in New York, Rudofsky proposed vernacular architecture. He had already tested the appeal of this subject in an exhibition of his travel portfolio at the Bauausstellung in Berlin in the 1930s. However, the exhibition was rejected as unsuitable for a modern art museum, and a copy of Rudofsky’s portfolio remained buried among MoMA’s documents for another 23 years.

In the 1960s, the climate had shifted slightly, but it still took the lukewarm interest of José Luis Sert, Gio Ponti, Kenzo Tange, Richard Neutra, and the crucial support of Pietro Belluschi, then dean of MIT, to secure Rudofsky a scholarship and allow him to complete the preparatory work for the exhibition.

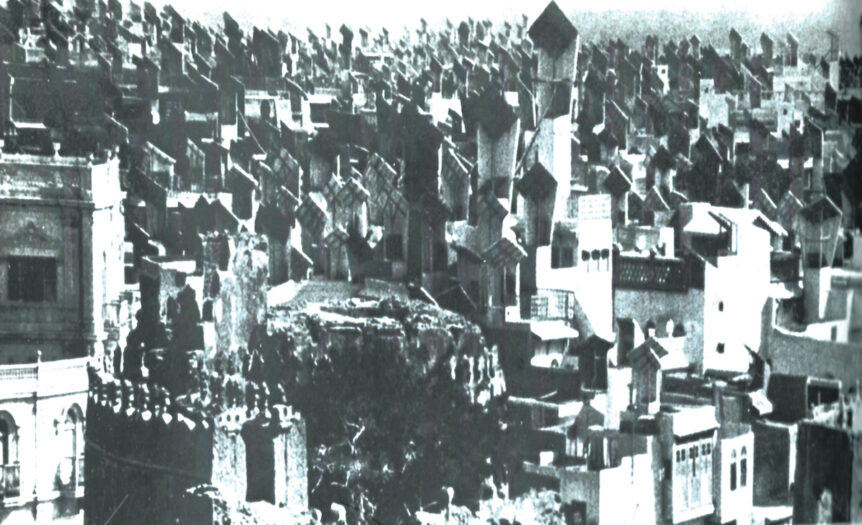

The exhibition was groundbreaking: could architecture without architects have achieved, over the centuries, what distinguished architecture—an expression of an increasingly globalized world—could never have achieved because it was unresponsive to the necessity of living in harmony with nature? The answer shook the foundations of that power and wealth that still sustain the mainstream architectural system. The exhibition also demonstrated how vernacular architecture was a marvelous expression of human ingenuity—an art not confined to a few elites—and the highest expression of each place’s cultural diversity. Rudofsky also aimed to overturn another fundamental assumption of architectural history: the focus on analyzing predominantly Western architecture.

The “Other Moderns” and “Critical Regionalism”

The interest generated was such that the exhibition reached beyond the Iron Curtain and even to Australia: it traveled to 68 countries over 11 years, aiming to dignify ordinary people’s homes and view all vernacular architecture as the highest anthropological manifestation. Architecture without Architects was a guiding light for all those architects who, even without fully embracing Rudofsky’sextreme position, believed in a different path to modernity and looked to vernacular architecture in contrast to the arid functionalism of the International Style. They referred to places, felt the call of architecture as an expression of cultural diversity, and recognized the value and beauty of everyday spaces and objects.

The so-called “other moderns”, and even Robert Venturi’s experience, owe much to that first subversive exhibition. Through the extraordinary showcase of MoMA, Architecture without Architects became a voice for the change movements sweeping across countercultural America, from the environmental movement to the rejection of war and colonialism to the discontent with the already evident urban and rural devastations perpetuated in the name of modernity.

The step was short, and in the 1980s, the term “critical regionalism” was coined. Although Rudofsky did not intend architecture without architects as a model to imitate, generations of architects were profoundly influenced by it and, like good thieves, drew from those forms to produce the new.

The Current Legacy

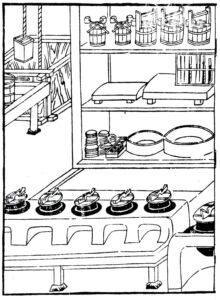

Rudofsky’s great lesson has opened the field to valuable contributions in practice and architectural history. Rereading Architecture without Architects in light of climate change shows that many of the answers we need today were already present in vernacular architecture, such as China’s underground cities or India’s wind towers. Credit goes to Rudofsky, and also to Giuseppe Pagano regarding Italy, for opening this wonderful Pandora’s box for everyone.

Reevaluate Architecture without Architects means filling in the gap in the discipline that, since Nikolaus Pevsner, separates the notion of architecture from that of building. To do this, as Rudofskyunderstood, we must turn to vernaculars. If we combine Rudofsky’s Warburgian memory associations with the contribution of vernacular architecture to architectural history, we can see how Architecture without Architects has broadened the field of art history and how it can continue to do so.

Archetypes for “Nameless Builders”

It is no coincidence that the Mediterranean, along with Japan, is the heart of all Rudofsky’sexplorations. The Mediterranean, particularly the Adriatic, represents a fault line between different cultures and is also the starting line for a vernacular architecture of good living, whose traits are still recognizable today. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that in the Mediterranean of the past 60 years, we find figures like Nail Çakırhan and Salima Naji, who have returned to contemplating materials, forms, traditional techniques, the relationship with the environment, and cultural aspects. In doing so, they have developed a timeless language that could be described as critical regionalism 2.0, where the architect returns to embracing typology and perhaps becomes a “nameless builder”.

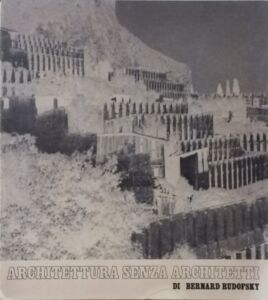

Cover Image: The “wind chimneys” in Hyderabad Sind, India (from Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York 1964)