A journey through the most prolific, diffuse production of the British architect, Pritzker Prize 2023, introduced by a foreword by David Chipperfield

Foreword by David Chipperfield

Receiving this extraordinary honour has been a wonderful surprise, and I am proud to associated with the previous recipients who have provided so much inspiration to me and to the whole profession. This recognition gives me great encouragement to continue directing my attention not only to the substance of architecture and its meaning, but also to reasserting the role our profession must play in addressing the existential challenges of climate change and societal inequality.

I firmly believe that architects must have a more prominent and engaged role in a more beautiful, fairer and more sustainable world. We must rise to this challenge and help inspire the next generation to embrace this responsibility with vision and courage.

Many of the most formative experiences of my career have been in Italy. I am deeply inspired by the architectural heritage of the country, of course, but also the strong culture of making. It is always a privilege to work with teams who cover so many skills and share a common dedication to quality of craftsmanship.

Pritzer Prize 2023 to David Chipperfield. Nothing will be as it used to be, according to many. Let’s venture into his museums, his most prolific production for places of culture, scattered throughout Africa, Latin America, China, Europe, Japan and the United States (including Alaska).

From the first, the Gotoh Museum in Chiba (1988), to the extension of the National Archeological Museum in Athens, which has recently won the competition, the architecture of the museums designed by Chipperfield become part of the landscape and go on to redefine the environment in which they stand. Faced with the image of his museums that blend new buildings and extensions, the feeling is one of free, extremely disciplined architecture that springs up like an improbable statement of fact, yet at the same time, is an intrinsic part of the actual landscape. His museum architecture appears to be a curated landscape project – urban or otherwise – which catalyzes what is intuitively perceptible, yet hidden, sparse and unrecognisable and, in the words of James Hillman, restores “the soul of the place”.

In search of the genius loci

At first sight, the Gotoh and the Athens Museums are very diverse in terms of their architecture, and as Chipperfield himself says, each building is an individual statement of fact in search of its genius loci. And yet, by seeking a key to their interpretation and assuming as a parameter the theme of a contemporary museum, a common feature filters through that embraces all his museum buildings: a sense of belonging to the landscape emanating from the museum settling as a Deleuzian “plateau”. This equally correlates all the immanent and temporary, human and non-human entities present, both in and outside the museum, of which the architecture is more the adjuvant agent. It is not a buffer, but “simply” an active, almost natural part of the process to re-understand,

The sticks-architecture

It was Chipperfield himself who provided an interpretative clue to his museum buildings when, in 2005, in an interview on the Museum of Modern Literature in Marbach (2001-06), he described the slender, linear articulation of the restricted, but airy, colonnaded gallery surrounding the museum as sticks-architecture. The gallery is the means with which to discern the landscape that unravels like a single sequence shot between the interior and the exterior, for which the sticks-architecture is the frame: a clear-cut geometry that in the complex of the James Simon Gallery (1999-2018) in Berlin, together with the Archeological Promenade of the Neues Museum (1993-2009), becomes the foundation, the urban planning tool for future projects for the Museum Island.

By widening or narrowing the focus on the colonnaded gallery and the promenade, the different nature of each museum unravels at the point where each is more or less accentuated. For example, the Gotoh Museum with its colonnaded gallery alongside the student accommodation block reveals the complicity between the museum, residence and university.

The embryonic image of sticks-architecture is visible in the texture that wraps around the building of the Figge Art Museum in Davenport (1999-2004) like an extensive system spelling out light gradations, and deformed in the amoebic membrane in the lantern of the MUDEC in Milan (2000-15). It acquires the strength of a structural and technological weave, capable of optimising energy resources – the existential challenge that pervades Chipperfield’s projects – in the pavilion of the Saint Louis Museum (2005-13), where the concrete grid of the roof acts as a casebook, a database with which to combine and dose natural and artificial interior lighting, and free up the layout with an uninterrupted view through the galleries out towards the surrounding landscape.

The comparison with Mies, “precision” architecture

The theme of a free, flexible floor plan relates back to the restoration and modernisation project (2012-21) of the Neue Nationalgalerie, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for Berlin (1965-68). Chipperfield emphasised the “precision” architecture of the free floor plan and the modern museum icon with his “Sticks and Stones” installation (2015). The Mies Room was both the place and the subject of the exhibition, the “stage and protagonist” said Chipperfield, who prepared a colonnade of 144 stripped, spruce trunks to give shape to the metaphor of a continual space between the classical, modern and contemporary. “Sticks and Stones” “defines rooms and panoramic views in the MIES Room”: Chipperfield’s words sound like a statement that can be extended to all his museum projects, with the possibility of opening the perception of nature (stones) to the imagination, by moving in a highly geometric form (sticks) that renders intelligible what he indicates as “the intrinsic qualities of the building: the arrangement of the structures, walls, enclosure, view, shelter and material”.

The constituent material is stones: the vertical, Jurassic limestone fins that segment the volume of the Kunsthaus in Zurich (2008-20), the statuesque blocks that soften the compact architecture of the Jumex Museum in Mexico City (2009-13), the “archaic” loggias into which the desert air is channelled in the Naga Site Museum (2008), a massive, gently stepped, camouflaged “wedge” emerging in an unspoilt, archaeological site; and the earthy, material consistency of the render that anchors the complex of pavilions and loggias of the Zhejiang Museum of Natural History in Hangzhou (2014-18) to the natural landscape.

The museum-agora in Athens, the latest result in a lengthy research

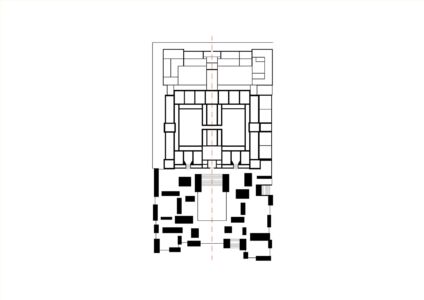

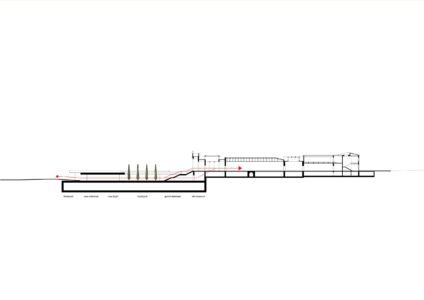

The new project to extend the museum in the Greek capital is the work that incorporates this lengthy research into architecture into the programme for the contemporary museum. This will merge with the existing museum: adapting to the standards of quality of the spaces, openness and sustainability, in a context strongly imbued with symbolic elements and historic references, of which the imposing, neoclassical architecture, designed by Ludwig Lange and Ernst Ziller (1855-74), is the emblem.

Chipperfield’s initial proposal is once again to redefine the environment around the museum. Leaving untouched the neoclassical building, he transposes a passive element, the base of the existing building, into a constructive element: its plinth extends over the street to add 20,000 m2 of new museum spaces. It acts as a foundation for the park, raised above street level and repositioned as a self-propelled frame around the neoclassical building, the resonance of which is highlighted in a rediscovered, urban, philhellenic environment, a museum-agora. Perhaps this is the unequivocal answer to the question that appeared at the opening of the Jumex Museum: what is the contemporary museum?

Cover photo: Render of the new National Archaeological Museum in Athens (© Filippo Bolognese Images)

About Author

Tag

ampliamenti , atene , concorsi , david chipperfield , musei , premio pritzker

Last modified: 18 Aprile 2023