On 24 January, Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi (1927-2023), the celebrated Indian architect and 2018 Pritzker Prize laureate, transitioned from this earthly realm, to what in Indian culture can be understood as a state of pure spirit at one with and indistinguishable from the essence of the universal dimension.

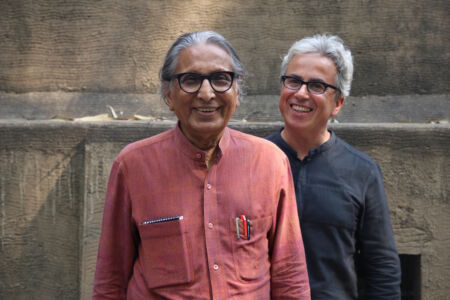

It was 1992 when landing in Ahmedabad, India, to begin an exciting experience at the Sangath Architecture Studio, I found myself sitting in an exotic garden. Surrounded by lush vegetation, unusual animals and pungent smells, I started sipping a bitter-sweet tea, the components of which were infused with the history of a complex thousand-year-old culture. The man in front of me had a sharp and profound gaze, spoke quickly and in a narrative manner. He observed, listened to, and did not speak to me about architecture. He exuded a strange charisma that induced respect but not distance. This resulted in a personal relationship which started with me joining his Guru for morning yogic practices.

Indeed, this was an unusual beginning from the eyes of a young Western architect who was nonetheless personally predisposed; thanks to this, we managed in a short time to break down all cultural barriers in favour of a shared humanity in which daily architectural practice is the means to ‘celebrate life’.

In 2019 at a workshop organized with Rajeev Kathpalia (Sangath Studio associate and Doshi’s son-in-law), the Vastu Shilpa Foundation (founded by Doshi in 1978) and Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University in China, the same charisma that attracted me in my youth now captivated a group of 30 Chinese and Indian students working in the spaces of the Mill Owners’ Association Building. These young people were enraptured by his stories in which Architecture became an ineffable space, a life experience and a meeting place between myth and reality.

Doshi walked with ease through the Mill Owners’ Association Building designed by Le Corbusier in 1954, and to which he contributed. The lessons that Doshi learned from his master Le Corbusier were consistently reinforced through the experience paths, movement, orientation and, along with these, order with its unpredictability, sensitivity to context, climate and the inclusion of an ecosystem made up of people, animals and plants. These were also integral and remembered as part of his childhood.

The experience of path, movement, orientation and, along with these, the rule with its unpredictability, sensitivity to context, climate and the inclusion of an ecosystem made up of people, animals and plants are some of the lessons that Doshi consistently recognised from his master Le Corbusier and that he also remembered as part of his childhood. His youthful experience was sometimes marked by dramatic events related to his health. During his time in Paris with Corbusier, he was forced to return home to India, this event making him for the rest of his life.

Nonetheless, Doshi, with sincere humility, always recognised this point as the start of a personal quest that would lead him to radically modify modernist approaches from functional to more regional sensibilities. Years later, he would say, “I became aware of the close give-and-take relationship between the land, resources, climatic conditions and people very early in my life. I also realised that our world consisted of distinct regions with characteristics that included different architectural practices unique to each region.”

In this short walk through memories of Doshi, I would like to go back a little further to 1987, when I met him in Siena at ILAUD. Since 1976, the International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design, founded by Giancarlo De Carlo, and the magazine Spazio&Società have provided forums for many personalities and universities from all over the world to meet and discuss themes and ideas initiated by TeamX.

On this occasion Peter Smithson, Donlyn Lyndon, Russ Ellis, Jan Digerud, Per Olaf Fjeld, De Carlo himself and many young architecture students participated, along with Doshi. This smiling little man, with his unusual features and fast speech wasted no time at all in recounting the plans for the ‘energy-conscious city’ of Vidyadharnagar, the garden-integrated spaces of Studio Sangath, the secrets of the Institute of Indology, the institute dedicated to Gandhi, and the unique path taken to build the Atyra low-cost housing complex for the homeless. With each project, each story, grew a mountain of limitless knowledge. As the images of Indian tradition merged with the experiences of Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn and Buckminster Fuller, my heart opened, I rejoiced, and my eyes grew moist. I remember an audience captivated and fascinated by the discovery that cultural walls could be broken down, that the world of the academies could be discussed, and that the most profound aspects of human nature could be seen and understood in a universal context.

“When love dominates,

Emotions take wings,

Immediate surroundings

become the field.

But to reach the skies

One must hear

The call from the stars.

There, indeed your dreams

wait for you.”

In silence, I spent the first few hours at Sangath, the studio in Ahmedabad, trying to organise the work table, which I later discovered was a copy of the one Doshi worked on in Rue de Sèvres in Paris. The parallel ruler, pens, pencils and light paper for sketches were the minimum equipment; the materials for constructing the study models were even more important. After a short while, I was joined by a young architect, Durganand Balsavar, now director of the Saveetha School of Architecture in Chennai and a scholar of Doshi’s work. With him I worked on a project for a new classical music school for Pandit Bhimsen Joshi in Pune. I remember a moment when Doshi sat at the table, spread the sketch paper over the plan, redrew it in pencil and quoted Le Corbusier said that the plan is a generator of ideas, but at the same time, drew signs and lines that were initially incomprehensible. After a while, my plan became the figure of Ganesh, the Hindu deity with a human body and an elephant’s head, whose long trunk generated a movement that would become the connecting ramp between the roof/auditorium and the sun-protected spaces below. I was incredulous and amused, and we all laughed at the alternative and complementary reading. Great lesson! Reality has many faces and can be read and perceived by multiple observers, but the important thing is what the architect layers into the design, the story he wants to tell. It is an invitation to experience, not in isolation, but together, because only in this way can architecture be defined as a ‘living entity’.

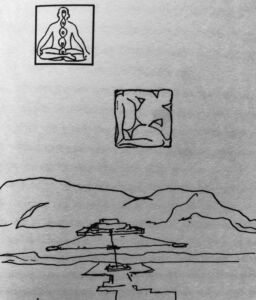

“An Indian Sthapati (Architect) has to be a yogi to feel the vibrations of every element in the cosmos, including the materials and the users of that space”.

Space designed with people’s different needs in mind makes ‘the building become an extension of life’; something Doshi has achieved in his own home, Kamala House, the CEPT University Campus, the Sangath Studio and many other buildings.

“Buildings are meant for people – which include literate, illiterate, young and old. Hence methods must be devised to establish a dialogue between the building and the users”.

Anyone who attempts to read Doshi’s work with academic or formal eyes quickly gets lost and thrown into a vortex of spaces with no precise boundaries, as in the Amdavad Ni Gufa Art Gallery. Only in the otherworldly dimension and through astral references can he find context and orient himself. The large eyes stretched towards the sky give internal relations, but at the same time, become an experience for a new landscape where materials ask to be touched with bare feet and hands.

“Form should not be finite but amorphous so that the experience within is loose, meandering and multiple”.

The tactile experience, the long paths alternating between intense light and deep shadows, the stone, the water, the oily sweat, the silences and the earthly bowels are some of the stories Doshi relates about travelling to the great temples of South India. At the same time, the geometric rigour and proportion of the compositional and structural grid refer to his work with Louis Kahn in the construction of the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmendabad. This experience would later be transcribed and interpreted in the Indian Institute of Management in Bangalore.

Another trip down memory lane takes me to Jaipur in 2015, to the International Conference ‘Crafting Future Cities’, where Doshi was the guest of honour. Some 20 years had passed since our first meeting and collaboration in the Ahmedabad studio. He still remembered me for our common yoga-related passions. Emotion prevailed over everything. What I remember most fondly were the pleasant chats spent reminiscing and the afternoon spent walking in the historical city of Jaipur. With his peculiar, hurried gait, he was curious, entering courtyards, talking to people, taking notes and sketching, inviting me to observe artisans’ work or taste the street food. A real lesson in humility and curiosity that leads him to affirm: what “I notice as I look back is a willingness to learn, being forever a student, and put in the hard-dogged work it calls for”.

This purely anti-celebrity attitude has deep roots in his training. Adherence to Gandhian principles is fundamental, “tempered by both the traditional ways as well as Gandhiji’s immense influence then on daily life, being frugal was second nature … this, in turn, promoted the virtue of being generous and giving because that was a more responsible way of living as a member of the larger community”.

Finally, in 2018, a few months before the awarding of the Pritzker Prize, I arrived in China. I saw a large exhibition at the Power Station of Art in Shanghai, specifically about Doshi’s work. I decided it was time to fix our association with an interview that could become a documentary. I immediately left for Ahmedabad, where a film crew headed by director Aditya Seth was waiting for me. Despite being in his nineties, Doshi was brilliant and kept up the long conversation. Outside the Sangath studio, in the garden, groups of students were waiting to spend a few minutes walking with him. I breathe quietly and walk beside him, lagging a little behind him; I see him fade into the younger generation. I imagine him strolling, his bare feet on the polished stone of a temple, where lights alternate with shadows in a perpetually repetitive and cyclical rhythm.

“Remember, without dark

night, there can never be

sunrise. Don’t even think

of only sunrise and smile

or think of only the darkest

night and imagine death.

They are both a part of you.

Accept nature and find the

positive and think of it as a

journey”