Giancarlo De Carlo was born in 1919, immediately after the First World War, grew up in the Fascist period, experienced the massive destruction of the Second World War in Italy, and was confronted with the political confusion and architectural dilemmas of the era of national reconstruction . He emerged from this chaos with a strong commitment to social improvement through architecture and urbanism. He navigated through the complex ideological currents of the post war period in search of a democratic expression appropriate to a rapidly changing and urbanising industrial society. In the creation of new infrastructures, social housing and educational institutions, De Carlo explored the tensions between city and countryside and developed ways of reading contexts as palimpsests containing overlapping historical layers. His architectural position involved both the extension and the critique of the primary lessons of the modern masters.

Like several of his generation, Giancarlo De Carlo rejected the dogmatic and diagrammatic urbanism of the CIAM (Congrès de l’Architecture Moderne) with its ‘functionalist’ separations of living, working etc, wishing instead to interpret social realities and particular places through a more complex spatial expression. In this, he overlapped with other architects associated with ‘Team 10’, although he himself insisted that each individual linked to this group posessed his or her own pedigree and architectural language. Giancarlo De Carlo shared with Aldo van Eyck an obsession with ‘spaces between’. Rather like his Danish contemporary Jorn Utzon (not affiliated with Team 10) he tended to consider individual buildings as inhabited topographies or social landscapes. Giancarlo De Carlo rejected the overt historicism of some of his Italian contemporaries but never lost sight of the importance of the past as an inspiration to be transformed. Via the filters of Le Corbusier and Aalto, he sought fundamentals in tradition, including both the vernacular and the historical townscape.

One of the ‘laboratories’ of post war Italian architecture was surely the replanning of Matera in the southern Italian region of Basilicata. Ludovico Quaroni’s new model ‘village’ of La Martella was to rehouse the poor inhabitants of the ‘Sassi’, the ancient troglodyte zone in the city center, in more sanitary conditions on a hill top site. As an architectural expression for this social and agricultural experiment , he adapted the ‘Neo-realist’ language of his Tiburtina Roman housing to the rural situation, providing the central church and and strings of houses with vernacular elements and angled roofs. In the mid 1950s several housing schemes were built on the fringes of Matera, among them the Residenze a Spine Bianche designed by Giancarlo De Carlo. In this case, the collective residences were laid out as parallel blocks with concrete frames, brick infills and overhanging tiled roofs. This effort at a ‘popular’ language implied a ‘rejection’ of tired CIAM official modernism and was probably indebted to the work of Franco Albini, particularly the INA headquarters in Parma(1950). But De Carlo was less successful in resolving frame, wall, and roof: in Matera he struggled to give his social aspirations an appropriate architectural form.

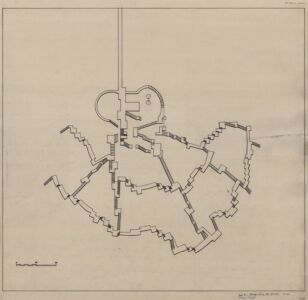

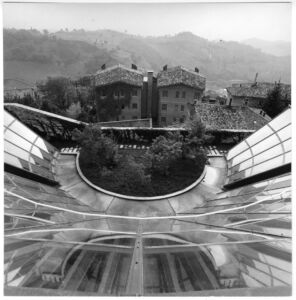

The project which put Giancarlo De Carlo on the international map was surely the complex of student residences for the University of Urbino, the Collegio del Colle (1962-66). He concentrated the communal functions in cylindrical elements on the crest of the hill, then linked these to splayed individual rooms by means of descending walkways affording spectacular views of the landscape and the old city of Urbino. De Carlo succeeded in abstracting the morphology of a traditional hill town in modern terms. Probably there were debts to Aalto in the fan-like configuration adjusted to the contours of the hillside, while the direct use of brick and concrete owed to Le Corbusier’s Maisons Jaouls. In my book Modern Architecture Since 1900 (1st edition 1982) I inserted the Urbino project in a chapter on critical transformations of Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Marseilles, such as the Siedlung Halen near Berne designed by Atelier 5. Its closest contemporary was probably Lasdun’s University of East Anglia (1962-4) which he referred to as an ‘urban landscape’, a term that could apply equally well to the Collegio del Colle. In both cases, the student residence was treated as an alternative city linked to nature.

Giancarlo De Carlo established an international presence through his activities with Team 10, through his texts and editorials (the journal Spazio e Società), through his numerous visiting professorships and through the summer seminars of his own ILAUD (International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design) in Urbino and Siena. He spoke English well, and this helped him disseminate his ideas internationally. I first met him in Cambridge Massachusetts in 1981 when he was a visiting professor in the Department of Architecture at MIT and I was teaching in the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard, the one building by Le Corbusier in North America, about which I had written my first book (Le Corbusier at Work, 1978). Catherine and I lived in a dusty wooden house tucked away behind trees off a track in north Cambridge. On Sunday mornings we ran an open house, a sort of continuous brunch, where people came and went . It was an informal forum on the current state of architecture and it was on one of these occasions that Giancarlo came to visit us. He felt at home in this atmosphere which was convivial but serious. I think he found MIT dull and a bit provincial.

Giancarlo combined great charm with a sparkling intelligence. He was somehow able to converse on a vast range of subjects while never letting his pipe leave his mouth. He dressed in a way that was casual yet elegant (I recall a rustic jacket with deep pockets) and he had something of the naval officer about him. Our conversations covered many subjects, including Le Corbusier (about whom he had written a book in the late 1940s), and the then current state of architecture in Italy. He detested the Venice Biennale of 1980, the ‘Presence of the Past’, with its pastiches of classical façades. He maintained, as I did, that the best of modern architecture transformed fundamentals from the past. He was skeptical about Aldo Rossi’s version of typology as this resulted in rigid geometrical formalism. He disagreed with the views of Manfredo Tafuri and was delighted to learn that I had written a scathing critique of Tafuri and Dal Co’s Architettura Contemporanea in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians (USA) in early 1981. Giancarlo’s enthusiasm for long term values of architecture was evident as was his skepticism about passing trends and fashions. When he referred to places, especially in Italy, it was as if they were old friends. He was concious of the long waves of history and the deposits of time in city and landscape.

Giancarlo De Carlo considered the traditional Italian city to be an amazing laboratory and source of knowledge in and of itself. He taught people to ‘read’ the historic fabric and to transform it. This was surely one of the central aims of the ILAUD summer school, initially in Urbino, later in Siena. This annual assembly attracted students and teachers from around the world in an agreeable setting where street and piazza became open air class rooms of a kind. In the mid 1980s Catherine and I were invited to the session in Siena and I spoke about Berber collective dwellings of the Northwest Sahara which I examined through multiple lenses and in relation to culture and landscape. I think that Giancarlo was quite surprised by this excursion into the oases of southern Morocco and the complex roots and meanings of these impressive mud fortified dwellings and urban forms. While we were in Siena, the ‘Palio’, the traditional horse race around the Piazza del Campo, took place: a demonstration in and of itself of the way a civic space could become an urban theatre for the re-enactment of an ancient ritual.

In 1989 Giancarlo and I met again, this time in a very formal, professional context. I was on a Jury in London for the Compton Verney Opera House Competition and persuaded the other members to interview him. On the jury were various grand Lords and Ladies and the meetings took place in a luxurious house in Mayfair. This was not Giancarlo’s world at all and the jury, which was leaning towards traditionalism and post-modernism, found his work rather spartan and stark. Despite the retrograde tendencies of the times, Giancarlo De Carlo was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal in 1993. In the mid 1990s I revised the 3rd edition of Modern Architecture Since 1900, this time adding his Institute of Education in Urbino, a subtle insertion in the historical fabric of the old. This was surely one of the clearest demonstrations of his architectural and urban philosophy. It was also a homage to Laurana’s and Francesco di Giorgio’s Quattrocento Palazzo di Urbino which Giancarlo admired for its enriching collisions of different spaces and fragments.

Giancarlo De Carlo remains in my memory as a committed architect with a sense of society, history, city and nature. His works speak for themselves and hold out many lasting lessons for those who take the time to study them. They are not isolated objects, but complex spatial insertions in the overlapping layers and interacting fragments of both city and landscape. They respond to existing places but without imitating them. They establish new coordinates, so providing both innovation and continuity. His masterpiece is surely the Collegio del Colle at Urbino, especially the first phase, a work which distills his social vision in a clear hierarchy of spaces, materials and forms. From the vantagepoint of the present, with its neo-liberalism, twisting skyscrapers and privatised urban space, Giancarlo De Carlo stands out as a sentinel of architectural principle and public responsibility. His legacy recalls a time when Italian architecture was based on more solid intellectual, social and political foundations.

© William J.R. Curtis 2020

Front page picture: Giancarlo De Carlo sketching while as usual smoking his pipe (Greece, 1972)