A brief visit to the Shed in Hudson Yards, part of a major development in Manhattan that has resulted in an orgy of new skyscrapers destined for office and residential uses, offers clues about the approach and outcome at the MoMA, given that they are both designed by the firm of Diller, Scofidio + Renfro. Purportedly an actual building, as opposed to the firm’s more usual commissions of restructurings, expansions, and general messing with existing buildings, the Shed contains a great performance space whose quilted enclosure carried on giant wheels could presumably move to open the performance room to the outdoors, and engage in dialogue with an immense mall rammed adjacent to it. In its potential for movement and transformation the design counters architectural solidity, but it is not the first building in the US to do so in recent memory. (The Milwaukee museum by Santiago Calatrava, who also excels in sculptural architecture, and daily opens its wings towards Lake Michigan.) This crowded scheme of architectural treats includes the curiously gratuitous Vessel by Thomas Heatherwick, essentially a stretched honeycomb-like jungle gym that offers visitors a tangle of staircases. Ascending the staircase (see link below) for which the author claims to have been inspired by the Spanish Steps in Rome, visitors enjoy an exhilarating and expanding view of Manhattan, the Hudson river, and the New Jersey shore (the last conventionally snubbed by Manhattanites, but of course Heatherwick is based in London).

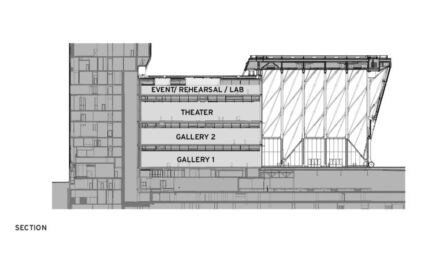

The Shed is an astonishing building that actually turns its back on the public square formed by the model and the skyscrapers and ornamented by the sculptural Vessel. Instead, the main entry to the Shed is from the High Line side, an outstandingly popular earlier intervention by Diller’s architectural team, that offers visitors a raised landscaped walkway through Lower Manhattan while keeping them off the street. One arrives into a great lobby, replete with the ubiquitous coffee shop, bookstore, and lounging furniture, much like a hip hotel. The “opportunistic design” claimed by the architects probably explains why despite its independence the Shed is not truly freestanding, burrowing under the nearest skyscraper, adjusting to the irregular geometries of the site, asking the visitor to go down into the lobby and then ascend to the main space. Its design is a collage-like approach to the history of modern art, offering constantly rearranged spaces in which to make art. From this lounge-like lobby one ascends to galleries, a theatre (really bleachers set into a space that could work as a gallery, or a homeless shelter, or whatever) and various studios, all large bare halls, bereft of markers or architectural detail, quickly abandoning the visitor to search in vain for spatial continuity and hierarchy. One novel use of the theatre is achieved by lifting the screen that separates it from the great court; the entire theatre then becomes a balcony that recalls the steeply raked seating overlooking Boston harbor from the Institute of Contemporary Art (also by Diller, Scofidio and Renfro).

From the lobby the main moving stairs take one up to the Shed itself, the great hall intended for social and artistic performances. Curiously, the main link of this performing arts building to the public square is through the Shed space, presumed openable, but in the meantime the actual link is a kind of afterthought — so coming from the Vessel, or arriving from the train station, the Shed is entered by a door through which one falls immediately into a dark hole containing the staircase that descends to the main lobby. Unlike anything else in New York, the alien building, awkward and ungainly, is riveted to a platform above the former train yard, in concert with the mall, the skyscrapers and the ornamental Vessel, isolated and hulking above the street grid of Manhattan.